Canola is one of the most misunderstood, mispurchased, and misused oils. Is it good for you? Is it good, or safe, to cook with? Is it right to cook with?

Canola is one of the most misunderstood, mispurchased, and misused oils. Is it good for you? Is it good, or safe, to cook with? Is it right to cook with?

It depends on what kind of canola oil that you use, and then how you use it in your cooking. Taking a moment to understand the stuff you use daily in your pantry can help make you a much better chef.

Canola has been sold for more than forty years as the wonder oil of home cooking. High in Omega-3s. Good for you. As my favorite waiter at the Second Avenue Deli in New York was fond of saying: “So, what’s not to like?”

Used incorrectly? Lots.

Mass Market Oil Savior

In 1974, Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford were president, All in the Family was the number one show on TV, animal fats were being identified by the medical community as the bogeymen of good health, and the other “big oil,” the vegetable oil producers, whom I call the vegoil cartel, were doing their best to leverage that fat fear to sell their wares.

Very little food product is moved on television these days, but in the 1970s the “fry wars” saw big guns like Crisco and Wesson slug it out. Whose oil made the best fried chicken with oil blends that were scientifically engineered.

Bland, high-temp and efficient were the names of the game. Frying was the biggest consumption of oil at home, so it became the focus of marketing by the industry.

Tidy convenience, at the expense of nutrition and authenticity in flavor, was how American consumption of cooking oil rolled, because pushing oils with taste or flavor required the manufacturers to source better quality seeds and nuts, and smaller production methods that didn’t max out the bottom line.

The vegoil cartel was taking the brunt of a lot of criticism of their Frankenstein oil blends, many of which were almost as bad, or possibly worse for your health as the lard they were trying to replace in the home frying game.

Safflower, hailed by doctors as the best and healthiest on the market, wasn’t cutting it. Expensive to produce and still having a distinct flavor, not ideal for frying, the vegoil cartel was still looking for its frying Holy Grail.

Leave it to our friends, those crazy Canadians, to fill the chalice with liquid gold…

WHAT IS CANOLA?

Canola is a form of rapeseed. In 1974, Canadian scientists, using cross breeding, rather than laboratory genetic modification, were able to create a better seed.

Rapeseed was used as an industrial lubricant in the U.S. Navy during WWII. It was cooked with, for centuries, before its mass-market introduction in the late 1970s, but it wasn’t as palatable, or as healthy, because it contained a high percentage, between 30% to 60%, of a substance called erucic acid, which scientific research associated with heart lesions in laboratory animals.

Still, it had other “good” properties. The studies on the health benefits of minimally-refined canola oil, decades ago, were legit: They found that it is high in antioxidants, unsaturated fats, and, as we began studying the value of Omega-3 fatty acids, we found out that Canola has that going for it too.

It was branded by the marketing people as “Canola,” a fusion of Canadian and the Latin word for oil, oleum, as rapeseed’s prefix “rape” had bad market mojo.

HOW IT’S MADE

All canola is made by crushing the seeds to express most of the oil.

ARTISAN PROCESS

In the Artisan process, traditional makers will roast the seeds in traditional heavy gauge kettles, and then use simple pressure-wheel mills called expellers to grind the seed, extract the oils, and leave it at that.

In the Artisan process, traditional makers will roast the seeds in traditional heavy gauge kettles, and then use simple pressure-wheel mills called expellers to grind the seed, extract the oils, and leave it at that.

You get essentially an “extra virgin” oil, although with anything other than olive oil, you generally don’t call it that, as the term is an industry branding thing specific to EVOO. The shorthand that the industry uses for this type of oil is Expeller Pressed.

There is still some oil left in the seeds after that first pressing, and our friends at the vegoil cartel want the rest of it. When you do that, what you get is a mass-produced, volume canola: An RBD.

MASS PRODUCED

RBD is industry shorthand for refined, blanched, and deodorized oils. For RBD canola, rapeseeds of any grade are used, including some rancid seed that finds its way into less scrutinized loads, and seeds often contain varying degrees of erucic acid.

It doesn’t really matter, though, because all of it is going to be scrubbed, purified, and descented until it drops into the bottle sitting in your pantry.

USING SOLVENTS TO GET THAT LAST DROP

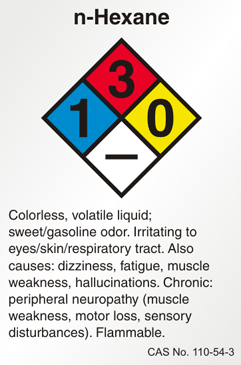

RBD canola will also have a second pass at the seeds with a low-boiling point chemical solvent, which is most often a petroleum distillate called n-hexane, a chemical distilled from crude oil. Pure n-hexane is a colorless liquid with a slightly disagreeable odor. It’s used in the food industry to release oils from nuts and seeds because it is efficient, evaporates easily, and dissolves only slightly in water. Aside from its uses in food, it is also a key component of biodiesel, glues and degreasers.

RBD canola will also have a second pass at the seeds with a low-boiling point chemical solvent, which is most often a petroleum distillate called n-hexane, a chemical distilled from crude oil. Pure n-hexane is a colorless liquid with a slightly disagreeable odor. It’s used in the food industry to release oils from nuts and seeds because it is efficient, evaporates easily, and dissolves only slightly in water. Aside from its uses in food, it is also a key component of biodiesel, glues and degreasers.

Your liver has enzymes that break down n-hexane. One of the products created by that reaction may cause damage to your

nervous system if you’re exposed to it over a long enough period of time, scientists tell us.

The EPA’s hexane report notes that chronic exposure can lead to nerve damage in humans. According to the FDA, that shouldn’t happen at the levels that it’s used by the vegoil cartel.

Infrequent exposure is common. It’s in gasoline, so people inhale more at the pump area than they may ingest. If you cook with RBD canola oils a lot over 20 years, no one has done much to study the cumulative effects of long-term ingestion of hexane. I’ve found that the research is also a little light on information about what happens when the oil is also synthesized into a purer form to increase its smoke-point temperature.

ADDING TRACE TRANS-FATS

To deodorize RBD canola oil, it is exposed to temperatures over its unrefined 93°C/200°F smoke point. That can create a small level of trans-fats, which are not good for you, and the FDA recently banned.

When it says “Zero Trans-Fats” remember that the labeling rules are skewed. If the amount is .05%, it really isn’t “0,” but you can legally say that it is. Of course, purified, it might come up to just under the 1% legal limit.

LESS OF THE STUFF THAT’S GOOD FOR YOU

All that processing reduces the Omega-3 fatty acids that canola manufacturers like to tout for their good health.

How You Bottle It Counts

Once it’s finished and bottled, most canola oil comes, inexplicably, in a clear plastic bottle, some not even BPA free. Highly processed RBD canola oil is very sensitive to light, which can easily degrade it. If it degrades, not only does it lose its some of its Omega-3 potency, but the the light breakdown, along with the over processing of bulk oils, can actually produce free radicals that can create negative health effects in the body as the oil breaks down.

Opaque bottles are best. If you don’t want to transfer your oil to one, then just keep it in a cool, dark dry place in your kitchen cabinet. Don’t leave it on the counter, and whatever you do, never leave vegetable oils in a kitchen window or an area that is exposed to a lot of heat, like your stove, or an area near a radiator.

BUY EXPELLER PRESSED ARTISAN OILS & USE WISELY

Canola is not your best bet for frying. Peanut, Avocado and Rice Bran oil are less processed, and have much higher smoke points and durability when heated to high temp. The latter two are best for everyday applications that you used canola to do, because neither has any strong taste. Pricewise, at $8-9 liter, both are reasonable everyday oils, with peanut for more specialized applications.

Artisan canola has a slightly nutty tone with a touch of bitterness on the back end. It is good in under 400°F applications, but I find, once it crosses about 93°C/200°F, it starts to get more and more burnt and bitter with higher temps or prolonged cooking.

Whole Foods, Fresh Market, and others sell inexpensive expeller-pressed canola. My personal pick, though, is La Tourangelle’s organic canola oil.

Whole Foods, Fresh Market, and others sell inexpensive expeller-pressed canola. My personal pick, though, is La Tourangelle’s organic canola oil.

Keep it in a cool room temp, dark place, NOT the refrigerator.

Canola oil, like all oils is best stored in an opaque container, like a can, although stores like to sell and store it in clear plastic containers.

It’s great in a lot of no-to-medium temperature applications, especially in emulsified foods like house my made fresh mayonnaise/aioli, which could turn even the biggest mayo hater into a lover.

It’s good in baked applications, like muffins, and I like it as the oil of choice for doing vegetables in a sous vide vacuum sealed bag, because it is both healthy and it works well in that long-time, low-temp cooking environment.

Since I generally slow-roast in the oven at low temp over a long time, I use Canola for some of my pork tenderloin roasts as well if I’m going nutty in the basic flavor of the fats.

WATCH THE SHELF DATES

Canola has a definite shelf life. Buy less of it, unless you make mayo in small batches regularly, as I advise, and use it up. It develops a stale taste after its “Best By” date that should be treated more like a “Use by” because of this.